The Congressional Globe

The Official Proceedings of Congress, Published by John C. Rives, Washington, D.C.

House of Representatives, 36th Congress, 1st Session

Feb. 29, 1859

The CHAIRMAN. When the committee rose it had under consideration resolutions of reference of the President’s message. On that question, the gentleman from Texas [Mr. Reagan] is entitled to the floor.

Mr. REAGAN. Mr. Chairman, I avail myself of the general range of debate, in Committee of the Whole on the President’s message, to discuss some topics which concern the whole nation. And, as I cannot expect to occupy the attention of the committee soon again under our rules, I shall have to try to discuss a greater number of questions than may be conveniently considered or clearly presented in one speech.

In the course of my remarks on the 4th of March last, when speaking of the purpose, and, I may add, of the determination of the Republican party to prevent the further extension of slavery in the Territories, I assumed that the Territories acquired since the formation of the Constitution, being acquired by the common blood and common treasure of all the people of all the Sates, were, as a logical and legal necessity, upon every principle of reason and right, the common property of all the people of all the States; or, to use another form of expression, that territory acquired by the mutual and joint efforts of all the people of the thirty-three States of the Union is, upon every principle of reason and fair dealing, the common property of all those who acquired it. I also assumed that the Federal Government was the agent and trustee of the people of these States, holding, regulating, and disposing of this common territory for their common and mutual benefit. And when the title to parcels of this territory passes out of this trustee, the Federal Government, to purchasers or settlers, it is always for a consideration which inures to the common good of all the people. The great and paramount object is the people. The great and paramount object is to furnish homes for the people on easy terms. And when I say homes for the people I mean, of course, homes for the people of any and every part of the Union,; and not that the territory acquired by the people of the thirty-three States is acquired for the benefit of the seventeen free States to the exclusion of the fifteen slave-holding States, any more than when the public lands are sold, the purchase money should go into the hands of the people of the seventeen free States instead of into the Federal Treasury, as the means of the whole people.

If I am correct in this, and I presume no one can doubt that I am, I ask if any act of Congress which would divert the proceeds of the sale of these lands from the common Treasury, and apply them to the exclusive use of the people of the seventeen free States, would not be clearly unconstitutional? And if this question be answered in the affirmative, then I ask if any act of Congress which would limit the right of settlement on these lands to the people of the seventeen free States, to the exclusion of the people of the fifteen slave States, would not be equally unconstitutional? And if this question be answered in the affirmative, then I ask if any act of Congress which would exclude the any given number of the people from a right of settlement secured to the remainder of them, would not also be unconstitutional? And if this question be answered in the affirmative, would not any act of Congress which should impose onerous and burdensome disabilities on the people of the slaveholding States, affecting their right to settle in the Territories, or creating a legal condition, express or implied, which should not apply to the people of the free States, and requiring a compliance with it to enable them to settle in the Territories, be also clearly unconstitutional? And if this be answered in the affirmative, I ask, if Congress or a Territorial Legislature should pass an act abolishing slavery in any of the Territories, if such an act would not impose upon every slaveholder, as a condition of his right to settle in any such Territory, the necessity of selling or freeing his slaves? And if this question be answered in the affirmative, would it not follow, as an inevitable and logical consequence, that such an act would be unconstitutional and void?

I beg to be understood as not putting these propositions for any purpose of controversy, but solely for the purpose of drawing out and establishing, by fair statement and logical deduction, the fact that neither Congress nor the Territorial Legislatures have the power to abolish slavery in the Territories.

It is admitted by the Republicans that they have no power over the subject of slavery in the States. And if it can be shown that they have no power of the subject of slavery in the Territories, while in a territorial condition, then they country will judge whether they are excusable for a longer continuance of their unlawful, irritating, and dangerous agitation of this question, and whether they should longer insist on an unconstitutional restriction on the rights of their fellow-citizens, which, if carried out, would brand the people of the fifteen States with inequality of rights under a Constitution which recognizes them as equals, and thus drive them to degradation and dishonor in the Union, or independence, equality, and self-respect out of it.

I do not propose now to reply to the declamation we so often hear in this Hall on the abstract question of /freedom/; but may submit a word of inquiry as to what freedom is, as applied to the people of the United States, composed as they are of two races, with capacities so different, that what to one is liberty would to the other be unbridled anarchy and licentiousness; and will call attention to the fact, that those who engage in this fugitive declamation about freedom, and

the crime of slavery, as they call it, never dare come up to the real questions they have raised. They excite the passions of the fanatical and ignorant, by wild and reckless declamation, and shrink back appalled from such questions as real statesmen have to grapple. They do not recognize the fact in their discussions of the existence of two races of men in the country, differing in color, differing in physical conformation, differing in intellectual capacity and endowments, and differing in the quality of their moral perceptions. For the purpose of agitation, they treat all as equals; and yet they dare not acknowledge the negro equal to themselves. Even Mr. Giddings would not acknowledge this last session, when pressed on the question by his colleague. And, to-day, I have no doubt, that if negroes of the South could be freed, on the condition that they should be sent to live in the free States, and the question were submitted to the Republican party whether they would consent to their freedom on these terms, they would with almost entire unanimity refuse the negroes their freedom.

And yet they pretend it is a crime in us not to set them free, at our expense, and submit also to allow them to remain among us, or undertake to find homes for them elsewhere, at our own expense. They do not recognize and consider in their speeches the fact that there are four million of these negroes; that they are incapable of self-government; and that to invest them with freedom would necessarily lead to the extermination of the greater part of them for the safety of society and the preservation of real, intelligent, regulated liberty to the people of fifteen States of the Union; and the relapsing of the remainder of them into the condition of degradation, suffering, and want, in which the free negroes of the free States, and of the West Indies, are now wearing out their miserable existence, in a hopeless competition with a superior race in the one, and for the want of intelligence to direct and control them in the other. Nor do they consider the fact that these four million negroes represent, in the hands of their owners, two thousand million dollars ($55.24 billion in 2016); which, in itself, is a valuable investment of capital, and in their opinion, improving and elevating the negro morally, intellectually and physically, and adding to the prosperity and happiness of the white race. A statesman, when he proposes an act, considers its end. Do these gentlemen, when they propose freedom to the negro, consider in what that freedom must end? Why, sir, so well do they know their weakness, on these great questions, that they dare not discuss them. They have not, and they will not, attempt to tell what is to become of the negroes if set free. They have not, and they will not, attempt to tell how they will free them in the States. And they only propose excluding them from the Territories by a violation of the great charter of American liberty, the Constitution of the United States, which they have all sworn to support. Thus proving, by their own want of good faith in violating the most solemn of human compacts, their own incapacity for free, self-government. For no people are fit to be free, or will long remain free, who cannot understand, or will not maintain their political compacts.

It is assumed by some that the power of Congress to legislate for the Territories, carries with it the right to mold the institutions of a Territory, and hence to abolish slavery; and by others, that slavery is a creature of local law, and that is cannot be carried into the Territories and maintained there without the aid of positive local law; and by others still, that, while slavery is recognized by the Constitution, and may go into the Territories under its protection, and cannot be abolished in the Territories by Congress, that yet, under the authority of Congress conferring on them the right to regulate their domestic institutions, subject (to use the language of the Kansas-Nebraska bill) to the Constitution of the United States, they may abolish it.

Either of these three modes of getting rid of slavery in the Territories involves two highly important questions. The one, the right of all people to an equal participation in the settlement of the Territories, the common property of all. The other, the power under the Federal Constitution to destroy private property. The first assuming that the people of the United States are not equals in their rights under the Constitution. The second claiming an absolutely despotic authority, such as few despots would dare exercise in this age of the world, even over the most subservient people, under our republican Constitution, frame to secure and preserve the equal rights of all people under it; and that, too, when the Constitution provides that

“No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.”

A Constitution conferring but limited and strictly delegated authority to Congress, and declaring that “the enumeration of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people,” and that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people;” and which says, in its preamble, it was “ordained” to “establish justice” and insure “domestic tranquility.”

It is also said that if the power be conceded to Congress to legislate for the protection of slavery in Territories, it may, under the power to legislate on the subject, abolish slavery. The power to destroy property in slaves no more follows the authority to protect slave property, than does the power to destroy commerce follow the authority “to regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes;” or the authority to take from a citizen his money under the power “to coin money and regulate the value thereof;” or the right to sink our national ships in the ocean under the power to “provide and maintain a navy;” or the power to imprison the citizen and confiscate his property for “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable search and seizures.”

Again, the Republicans declare broadly that they do not recognize the right of property in man. Which can only mean that they deny the authority of the Constitution; and, in their perverse determination to agitate, appeal to a “higher law.” And this declaration is made in the face of the history of negro slavery in this country before and since the formation of the Constitution; in view of the fact that the Constitution provides for the capture and return of fugitive slaves, on account of the proprietary right of the masters to their services; in the face of the fact that the Constitution provided that the African slave trade should not be prohibited for twenty years after its adoption, in order that the people of the United States might acquire still greater amount of property in slaves: and when it authorized the imposition of a tax not exceeding ten dollars a head on those which were to be imported, thus deriving a part of the revenues of the country from their importation; and in view of the further fact that at the date of the Declaration of Independence the right of property in negro slaves was recognized in every one of the States then declared to be free and independent; and that at the time of the adoption of the Federal Constitution every State but one still recognized the right of property in negro slaves, and their citizens then bought and sold, and held and owned them as property, and that they passed by inheritance and sale among them just as any other property.

And here I may say that a very large part of the slaves, whose descendants are now owned in the South were brought from Africa and sold into slavery, as property of course, by the fathers of the men who now talk so loudly about the crime of slavery. This shows a difference of opinion between the fathers, in the now free States, who helped form and adopt the Federal Constitution, and their sons, who repudiate its provisions, as to the right of property in negro slaves. And it should also be borne in the mind that the people of the free States, instead of freeing their slaves and allowing them to remain among them, as they would have us do, sold most of them to the people of the present slave States, and received their value in money, and thereby relieved themselves of the unpleasant thought of having to indulge in the luxury of abolitionism at the expense of any pecuniary sacrifice to themselves.

And again we are met by the Republicans with the statement that the Declaration of Independence declares that all men “are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” So it does; but this did not mean that slaves should be equal in authority with their masters, any more than that ladies should be legislators, judges, and generals; or that children should chastise their parents for disobedience. It was simply a declaration of political equality, so far as it has any political effect, of those who were parties to the political compact being formed. The same people in whose name the Declaration of Independence was made, ratified the Federal Constitution. Indeed, though they bore different dates, they are but parts of the same splendid and happy scheme of government. And a number of the persons who signed the Declaration of Independence aided in framing the Constitution. That Constitution did not enfranchise Indians, and make them our political equals. It expressly disfranchises such of them as are not taxed. It did not enfranchise the negroes and place them on political equality with the whites; for it recognized them as commerce and property, and provided for their return to service when they escaped from their masters. But this position, that the Declaration of Independence sanctions abolitionism, is precisely of a piece with the other, which refuses to recognize the right of property in negro slaves. They may only serve to amuse and deceive the ignorant, and as pabulum for political demagogues, but can excite no emotion in an enlightened and honorable mind but that of pity and contempt.

The Constitution may not be what these gentlemen wish it to be. But if it is not, they ought to endeavor to have it changed, and not attempt to destroy it by constructions which would contradict out whole past history, and involve its illustrious framers in the most shallow absurdities. If they are dissatisfied with our present Constitution and form of government, it is due to truth, candor, and fair dealing, as well as to their own dignity, honor, and statesmanship, that they say so plainly, and announce fairly the changes they desire, so that the people and the country may understand their aims and purposes, and act on them advisedly. It is unstatesmanlike, it is unmanly and unpatriotic, to attempt to subvert the Constitution by hypocritical and indirection, under the cover of deceitful generality, and by a studied evasion of a fair presentation, and free, open discussion of the real questions involved.

I wish now to call attention to some remarks which I submitted briefly, and without any previous arrangement of my thoughts, in the progress of the debates on the 4th and 5th of March; and to call attention to some criticisms on them, made by the gentleman from Connecticut [Mr. Ferry] in his speech on the 10th of this month; and to others, made by the gentleman from New York [Mr. Fenton] in his speech on the 16th of this month. I do this for the purpose of correcting errors into which those gentlemen seem to have fallen, and to protect myself against future misunderstanding; for it is evident that, whether they intended it for not, they did me manifest unjustice.

My position was, that the Constitution of the United States conferred no authority for the destruction of private property, either by Congress or a Territorial Legislature; and that negro slaves, being property, neither Congress nor a Territorial Legislature could abolish slavery in a Territory. I stated, at the time, that slavery might be abolished by the people of the States, in the exercise of their right of sovereignty, without any infraction of the Federal Constitution; and that it might be abolished by the people of a Territory, when they came to form for themselves, by a sovereign act, a constitution and State government. I also stated, in substance, that the authority to do so by a State, or territorial convention forming a State government, was not to be found in the Constitution and laws of the United States, or in reason or natural justice: but that, if done, it must be by an act of power, which I designed as a revolutionary act, resting upon an authority superior to that of the Constitution and laws, and independent of them; inasmuch as the authority of the people who form States, is superior to the authority of the States they form. And though, by such an act of sovereignty, private property may be destroyed, I insisted, and still insist, that it would be one of arbitrary, despotic power—a revolutionary act—resting for its authority not upon the Constitution and laws of the United States, for there is no such power or object in them; not upon the spirit

and object of State constitutions and State laws, for they are instituted for the protection, and not for the destruction of private property and personal rights; not upon the rules of right and reason, which, through all our constitutions and laws, protect the persons and property of the people against every usurpation of mere arbitrary power by Government; but it exists in the original, inherent /power/ of the people to do it right or wrong, as they may /will/; to institute a just, benign, and liberal system of government, and provide for the protection of all the rights of the people who form it, or to inaugurate the reign of anarchy, or institute a despotic form of government, which, instead of recognizing the rights of property of the people as they find them, shall destroy the property of a portion of them to gratify the caprices or passions of the balance. Such an act would destroy preexisting private rights; and, in doing so, would be against the spirit of all our constitutions and laws. And it is only because there is no tribunal to which an appeal against such an act of sovereignty can be had, and because the aggrieved and injured minority, in such a case, have not the power by numbers or arms to maintain and vindicate their rights, that they would submit to its exercise.

This is the spirit and substance, somewhat amplified, of what I said on the occasions referred to, and in my reply to the gentleman from Connecticut [Mr. Ferry] on the 10th of this month.

I shall, after awhile, refer to some authority to sustain the positions that the right of property is recognized in negro slaves by the Federal Constitutions, and that neither Congress, or a Territorial Legislature, can abolish slavery. And though, in the hour allowed me, I can expect to do but little more than state my own views on the question presented, I shall be content if they in any degree commend themselves to the confidence of others by their inherent reasonableness and justice, and by their conformity to the principles of our Constitution, and they theory and genius of our Government and institutions; and especially if they shall have any effect in calling attention to the real questions involved in the sectional controversy which has so long and unhappily prevailed in our country. For if we can succeed in determining our relative rights and duties, and in ascertaining the real questions at issue, then the public judgment can be fairly taken on them, and the question will be decided whether we are to respect the rights of each other, as citizens of a common country, living under a common Constitution, and looking hopefully and proudly to a common destiny; or must, on account of an irreconcilable conflict of interests and opinions, be separated for the future.

The gentleman from Connecticut, in his well considered and eloquent speech, professes to give the doctrines of the Democratic party in relation to the powers and duties of the Federal Government over the subject of slavery. Others may answer whether he gave them fairly, for the purpose of controverting the real positions of that party, or totally misrepresented them in order to give plausibility to the doctrines of the Republican party. Among other things he says, “It holds as an abstract proposition, that property in man exists of natural right.” This will doubtless go the rounds of the Republican press, and be used by them to deceive Republican constituencies, and constitute a part of the staple of the campaign speeches of that party this summer and fall. And as it doubtless had its origin in a misunderstanding of what I said, I desire now to correct it. And I wish now to say, that no national or State convention of the Democratic party, and no county or township meeting of that party, nor any member of that party, including myself, ever amounted to any such principle, within my knowledge; and that I do not think the gentleman can sustain his assertion by the production of any such authority for his statement.

It is true, I used the expressions “natural right” and “natural justice” in my unpremeditated answers to questions unexpectedly propounded by the gentleman from Massachusetts, [Mr Gooch,] in discussing the power of Congress and of the Territorial Legislatures to abolish slavery. I used them in several forms of expression; and am now satisfied that, in some of these, I used the word “natural” unnecessarily, but nowhere in the sense in which the gentleman uses it in the above extract. My purpose was to convey the idea that it was against reason and justice to deprive any man of his right of property, whether in slaves or other things, against his consent and without just compensation. It certainly was not my purpose to describe the character of right by which any man holds any kind of property, for I was speaking of a wrong, and that wrong the destruction of private property. For instance, I said, in form and expression, referring to the power of the States to abolish slavery—

“That they have the right, but that it is a revolutionary right, and not a right resting upon law or upon natural justice; and when a Government comes to exercise its sovereignty, and undertakes in its sovereign capacity to destroy that right, it departs from a great principle, which ought to govern it always. It should protect the condition of society when the Government was formed, and should protect all the property of the people who form that Government, destroying none of it.”

And again I said:

“The exercise of any revolutionary right which destroys private property, is a violation of the principles of natural justice.”

But if I am mistaken as to the effect of any language I may have used in a hurry of debate, I wish now to declare that all I desired to do, was to describe the rights of persons and insist on their protections, without even thinking of, or wishing to engage in any controversy about any distinction between legal and natural rights, or legal and natural justice.

I do not wish to be understood by this, as saying or admitting that property in slaves does not rest on as high authority, and as just principles of right as any other property; for I think it does. But only that it is not necessary to discuss the question of whether we hold any kind of property by the principles of natural right and natural justice, as contradistinguished from the social customs, political principles, and maxims of jurisprudence of a people. I am only now considering our practical duties as legislators.

If the Democratic party has ever gone out of the field of politics to settle abstract questions of philosophy, or questions of natural rights as contradistinguished from political questions, I have never heard of it. It certainly is not to be found in the platforms which embody the principles and opinions of the party. It deals only with the political relations of the country, and in doing this takes the Constitution as its polar star and guide. It is neither a pro-slavery nor anti-slavery party. A man may be a good Democrat and approve of slavery as in itself right, or disapprove of it as being in itself wrong. But it is a part of the creed of the Democratic party to respect both the rights of the States and the rights of the people. And hence a man cannot be a Democrat, who, in disregard of the rights of the States, would engage in agitation in one State to force slavery out of or into another: or who would attempt, through the agency of the Federal Government, either by direct or indirect means, to retard or promote the interests of slavery in a State; or who would attempt to use the Federal Government as an agent for the destruction of private property, whether that property be in slaves or other things.

And the doctrine of the Democratic party, with reference to this subject in the Territories, is, that

“They shall be left perfectly free to form and regulate their domestic institutions in their own way, subject only to the Constitution of the United States.”

I know that this part of the platform has given rise to discussion, and there are among Democrats differences of opinion as to its meaning.

I know that this part of the platform has given rise to discussion, and there are among Democrats differences of opinion as to its meaning.

My own construction of this part of the platform, and of the corresponding part of the Kansas-Nebraska act, is now what it was at the time of the passage of that act, and at the time of the action of the Cincinnati convention. That is, that if the Territories had power, independently of the superruling control of the Federal Constitution, then they might abolish slavery under that act; but that, if the provisions and efficacy of the Constitution pervaded the Territories as well as the States, they could not do so. It was understood in Congress, at the time of the passage of that act as well as it is now, that it did not define the powers of a Territory on this subject, but referred expressly to the Constitution as to what they were, by the words “subject only to the Constitution of the United States.” And it was then said and believed that a decision of the courts would be necessary to determine, under that act, whether those Territories could abolish slavery. And this very question has since been decided in the Dred Scott case, and the question put at rest. I had as full faith at the time of the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska act as I have now, that the Territories derived their powers to legislate from Congress, and could exercise no higher authority than they derived; that Congress had no authority to abolish slavery anywhere; and that, having no such authority, it could not confer the power on the Territories, on the principle that a principal can confer no greater authority on his agent than he possesses himself. And this is one of the leading grounds upon which we of the South sustained and approved the course of our members of Congress in voting for that act, and the main ground upon which we sustained the action of the Democratic party in securing its passage. And hence, when the Supreme Court of the United States made the decision in the Dred Scott case, we of the South experienced none of the surprise and horror professed by Republicans. We were prepared to expect such a decision on principle and reason.

We know, however, that many of the northern Democrats entertained opinions differing from these on that act and the part of the platform quoted. And there are strong reasons why we should be tolerant to their views on this subject, aside from the ordinary consideration of the unity of the party. It has been one of singular interest and difficult, upon which great and patriotic minds have differed. It required years of discussion to develop what we now regard as the true doctrine. And at one time the Democratic party supported for President a great statesman, the present venerable Secretary of State, who entertained a different view. But his opinion, and the position of the part on this question at that time, were developed from a different stand-point to the one from which we now view it. They were then inquiring whether the Wilmot proviso was not unconstitutional, and adopted the idea of territorial sovereignty as an incident to, rather than the main idea of, the contest; and without a full examination of those provisions of the Constitution which relate to personal and private rights. The question, as then examined, was mainly as to the political power of Congress and the Territories; and its consideration did not then extend to a full investigation of the questions which have since arisen, as to the effect of such a doctrine on the personal and preexisting vested rights of citizens, and their mutual right to occupy the common territory. It was the future development of these features of the question which corrected the former error of such of the party as subscribed to that doctrine.

An acquiescence now, in the doctrine of the decision of the Supreme Court, will place the party on this question on an enduring basis, alike constitutional and just to all parts of the Union, and calculated, if anything can do so, to secure a suspension of sectional agitation on this question. And this is an easy basis on which to secure the harmony and unity of the party; for no one should feel humiliated by giving his assent to the judgment of the highest judicial tribunal in the Union on a purely judicial question.

Again, the Democratic party, recognizing its obligation to obey the Constitution, is also in favor of the enforcement of the fugitive slave law. But there is no principle of reason upon which it can be said, because a citizen feels bound to observe and obey the laws of the land, in the rendition of fugitive slaves, that he is therefore committed to any particular abstract doctrine on the subject of slavery.

The last national Democratic convention adopted the following resolution as one of the articles of faith and practice of the party, to wit:

“Resolved, That we recognize the right of the people of all the Territories, including Kansas and Nebraska, setting through the legally and fairly expressed will of the majority of actual residents, and whenever the number of their inhabitants justified it, to form a constitution, with or without domestic slavery, and to be admitted into the Union on terms of perfect equality with the other States.”

And this patriotic and just principle is now subscribed to by the Democracy of every State in the Union, as securing the equal rights of all in the Territories, and the power of the people at the proper time, and in the proper way, to settle the slavery question for themselves. The successful maintenance of this principle would be the means of antagonizing the sectional and unconstitutional idea of the Republican party; and of thus giving

repose to the country, securing the preservation of the Constitution and the perpetuity of the Union.

Another of the principles of the Democratic party, as set forth by its last national convention is:

“That the Democratic party will resist all attempts at renewing, in Congress or out of it, the agitation of the slavery question, under whatever shape or color the attempt may be made.”

It is now the policy of the party to prevent all agitation on the subject. And it is the sincere wish of the great mass of the people of the South to see this agitation brought to an end. They only wish to have their constitutional rights respected, and to be let alone. Neither they or the Democratic party of the nation desire to promote any schemes of aggression for or against slavery.

The Republicans charge aggression on the Democracy, and on the South: but they know there is not a word of truth in the charges: and they only make it to deceive their own people, and give a pretext for, and plausibility to, their unconstitutional and fanatical crusade against the South, fearing, doubtless, that unless they can deceive their own people into such a belief, they cannot maintain the present dangerous ascendancy of their party.

The Republicans, to sustain this idea of southern aggression, and that the Democratic party is a southern sectional party, would implicate both in a purpose to reopen the African slave trade. And they do this in the face of the above resolution of the national convention, against the agitation of the question of slavery in any form, in Congress or out of it; and in the face of the fact that nine tenths or more of the Representatives of the southern States, and every northern Democrat on the floor, are opposed to it; and in the face of the President’s late message, which takes strong ground against it, and urges increased efforts on the part of the Government to prevent any unlawful continuance of the traffic. Speaking for myself on this subject, coming, as I do, from an extreme southern State, I took strong grounds against this trade by my late canvass, and was sustained in it by the general sentiment of my district.

Now, this is a fair statement of the doctrines of the Democratic party, as far as they relate to the question of slavery. And this shows that, with all of the apparent fairness of the gentleman from Connecticut, he has misstated the doctrines of the party, and argued against fancied evils which have no real existence. I will read an extract from his speech, for the purpose of noting some other errors into which he seems to have fallen:

“From where, I may ask, did the people, while in their territorial condition, as they must have been while in the act of making their constitution, acquire the power to abolish slavery in their borders? From any inherent right to do so? This is vehemently denied. From any act of Congress? It is expressly affirmed that Congress can confer no such power. From the Constitution of the United States? The answer is an unqualified negative. Whence, then, does this power come. The gentleman from Texas, [Mr. Reagan,] in his very able speech, gives only the answer which, upon Democratic theory, the question is susceptible. The power is a revolutionary one, against all constitutions, all laws, all governmental authority; it comes by revolution. The whole Democratic territorial policy is thus reduced to a system, not of order, but of disorder; not of regulated law, but of chronic anarchy; not of peace and stability, but of ‘resolution.’

“Such are the fundamental principles of the Democratic party, and such its logical results.”

Now, there are two capital errors in the portion of the gentleman’s speech here quoted. The first, in his order of presenting them, is the assumption that, when a territorial convention, in framing a constitution preparatory to being admitted as a State, provides for abolishing slavery, it is the abolition of slavery by the people of a Territory. The answer to The answer to this is, that such an act does not take effect while the people remain in their territorial condition; and it is, therefore, not the act of the people of a Territory receiving its vitality from them while they remain in that condition, but it is only the preliminary action of the people, indicating a thing, not done, but which is to be done, when, and on the condition that, Congress gives its consent to their admission into the Union as a State, and their consequent investiture with the attributes and sovereignty of a State. It then becomes the act of a State, through its organic law; and not the act of a Territory, as such.

Congress can only legitimately inquire, in examining the constitution of a State applying for admission into the Union, whether it be republican in form; and cannot reject its application because its people may have chosen, in the exercise of their attributes of sovereignty, to disregard and destroy private rights.

His other great error is in assuming that the theory which supposes slavery can only be abolished by the authority of State sovereignty, and private property and vested rights destroyed by what I call an act of revolution, is the recognition by the Democratic party of a theory in conflict with all constitutions and laws and governmental authority. Now, exactly the reverse of this is the position of the Democratic party. It respects the Constitution and its guarantees, and therefore refuses to violate them by assenting to powers not delegated, for the purpose of destroying the private property and vested rights of citizens. It respects the authority of States, and therefore will not attempt to interfere with them for exercising the attributes of sovereignty, however harshly, toward their own citizens. And it rightly limits the power to destroy private property and vested rights to the original sovereignty of the people—to their revolutionary right to change, alter, or abolish their forms of government.

And in this, upon this question, consists the great difference between it and the Republican party. That party would violate the Constitution by the exercise of authority by Congress nowhere to be found within it, and by a direct disregard of those of its provisions which guaranty the security of private property and vested rights. It would violate the principles of law and equity by denying to the people of one half of the States an equal participation with those of the other half in the settlement, occupation, and enjoyment of the Territories, which are the common property of all; and it would disregard all governmental authority by employing the revolutionary power to destroy private property and vested rights as one of the appropriate objects of their creation.

The difference between the gentleman and myself is, that he would inaugurate the employment of the revolutionary power to destroy private property and vested rights, as a lawful and constitutional means of accomplishing the Republican purpose of excluding slavery from the Territories; while I resist this as violative of the Constitution, and insist that this revolutionary power can only be exercised by a people in their sovereign capacity, by virtue of their inherent right to change, alter, or abolish the existing form of government.

In support of the theory that one of the great objects of Government is to preserve private property and secure vested rights, I refer to the fact that neither the Federal Government nor the Government of any one of the States of the Union has omitted to guard them strictly against the power of the legislative authority. And to omit this in the constitution of any Government would be to omit one of the most important safeguard of liberty and one of the strongest bulwarks against despotism. The struggles between Governments and people are nearly always between power on the one side and right on the other. And hence we limit the powers of our Government by written constitutions for our protection in such struggles; and these, if observed, secure our rights against everything but an appeal to original sovereignty—the government-making power.

Upon the predicate that the Democratic party maintains that “property in man exists of natural right,” and that it takes all the grounds necessary to sustain slavery as right, expedient, and just in the abstract, the gentleman from Connecticut says:

“If these principles be correct, there is no justification or palliation for the laws of the United States against the African slave trade.”

I have already said that the Democratic party is neither a pro-slavery nor anti-slavery party; and I have tried to show that it has taken no position on these abstract questions, and only feel astonished that the gentleman should it had done either.

For myself, (and in this I speak only for myself,) while I do not occupy the position the gentleman would improperly assign the Democratic party on these questions, I do believe, whether the African slave trade be right or wrong, and whether slavery as it exists among us be right or wrong in the abstract, the people of the free States have nothing to do with it as it exists in the slave States, and have no right to interfere with the subject; and that such an interference on their part, whether by agitating or attempts at practical action, is an impertinent, unjust, and unwarranted intermeddling with the affairs of others, in open disregard of the principles of the Federal Union; and I believe further, that, as practical legislators, those who have this institution, and the consequent right to deal with it, must consider it and deal with it as they find it, without going back to inquire whether its origin was right or wrong.

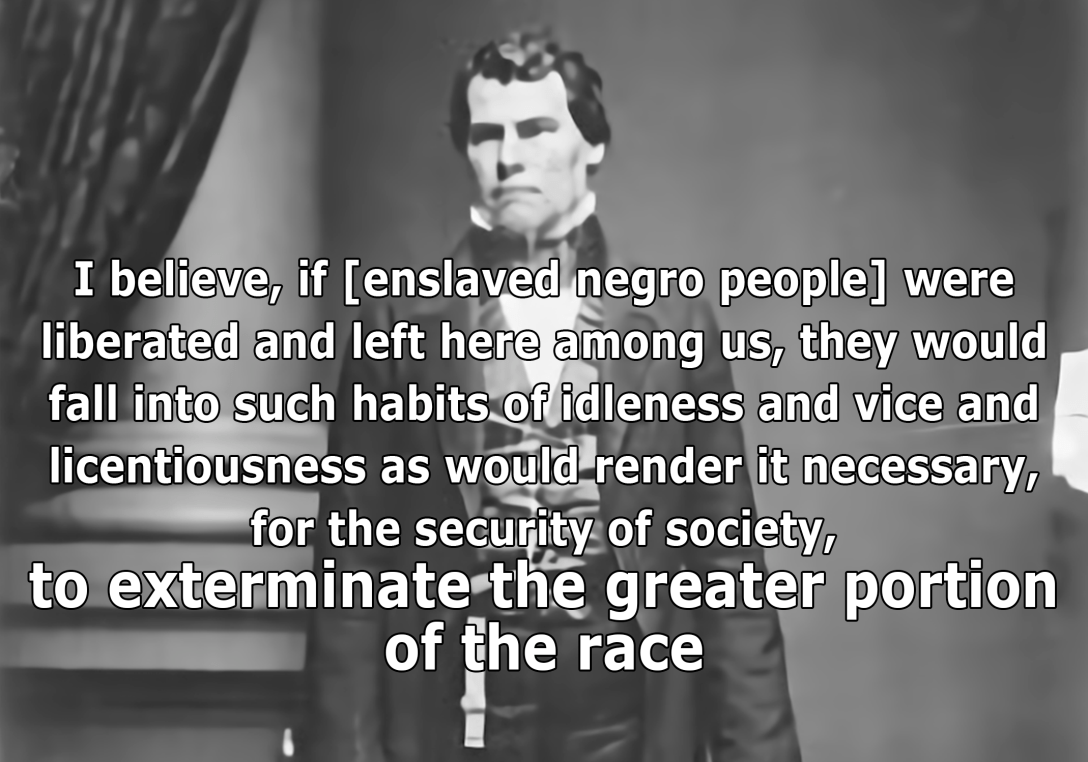

I tell the gentleman I do not believe slavery, as it exists with us, is either a crime or immoral, whatever its origin may have been; but that I do believe it would be a crime against reason and humanity, taking into view the condition of our Government and society as we find them, and of the condition and capacities of the negroes as they are, to set them free. I believe this because I believe the four million negroes in bondage in this country are better fed, better clothed, better protected from violence and wrong, better informed, more intelligent, and possess more religious advantages than any other four million of that race on earth; because I believe them, as a race, incapable of self-government; because I believe, under providence of God, they are now going through a training which is elevating them in the scale of humanity, and, at the same time, aiding the white race to develop a great and splendid civilization; because I believe, if they were liberated and left here among us, they would fall into such habits of idleness and vice and licentiousness as would render it necessary, for the security of society, to exterminate the greater portion of the race; because I believe that if we were to liberate them and send them away in a body to any other country, and leave them to their own direction, they would at once sink away into a state of anarchy and crime, and from that to a state of heathenish barbarism.

But it is far from following as a matter of course, because I believe this, that I should advocate the reopening of the African slave trade. The slave trade encourages the tribal wars and the consequent cruelties in Africa, and those who engage in it are accessories to the crimes it produces. For this reason, I am opposed to it. And then there are the reasons resulting from the policy and interest of our own country, which I will not now occupy time to state, which induce me to oppose it. We are responsible for our treatment of the negroes we find among us. But this does not make it necessary or obligatory on us to extend this responsibility by capturing others and bringing them here.

I will add thus more, that I believe any man who understands the condition, character, and capacity of the negroes, and who would advocate the freeing of them, in view of the consequences which much necessary follow it, would commit a crime against humanity, and be a traitor to his country. And that any man who madly or foolishly agitates this question, without understanding it, and without trying to comprehend what must be the result of his purpose if consummated, is a demagogue who deserves the reprobation and scorn of all honest men.

But, sir, what shall be said of the man who will so agitate to violate the Federal Constitution and dissolve and destroy the Union? Let the blighted hopes of mankind in the despotisms of the Old World, now looking to our Republic and longing to be free, answer. Let the expiring liberty of the millions of free, prosperous, and happy people of our own country answer. Let the future suspension of business, the political commotion, the neglect of agriculture, the grass growing up in school and church-yards, the shutting up of our manufacturing establishments, the destruction of commerce, the marshaling of armies, the bloody battlefields of brother against brother, the grief-stricken widows and orphans without hope of such as fall in these battles, let these answer. Let the glee of bloated royalty and hereditary nobility, over the fall of the republican equality and American liberty, answer. Let the war of political leaders and military chieftains, such as is now going on in Mexico, with no security for life or property, answer. And then let the dark, unvailed, bitter future bring up

its tales of tyranny, oppression, griefs, ignorance and woes, and make its answer. Sir, may God in His mercy open the eyes of the people of this country to what the demagogue politicians are doing and give them the wisdom to confound and virtue scorn them.

But I must not omit to notice briefly a portion of the speech of the gentleman from New York, [Mr. Fenton.] He also assumes that the Democratic party is a section, pro-slavery, southern party; and, among other things, he says the South now claims that slavery “must travel with the Constitution into the Territories, and there be sustained and protected by it.” He states this as if he regarded it as a novel claim. Has it come to this, that we are to be rebuked for claiming that the safeguards of the Constitutions are coextensive with out our national boundaries, and protect alike every citizen in his rights of person and property in the common Territories?

He then says, “I need not speak of the next effort to nationalize slavery,” and adds:

“The gentleman from Texas, [Mr. Reagan,] a few days since, with disingenuous boldness, indicated one of the advance steps the Democratic party will soon take; and I could, therefore, claim no credit for the discovery in this instance. If I understood him correctly, he claimed that not even State authority—State sovereignty—can abolish or impair the right of property in slaves short of revolution. That is, the right to abolish would be a revolutionary right; that its claim for protection under Federal and State authority rests upon the same right as all other kinds of property. Indeed, I do not see why this is not a logical sequence from the premises. Then it is, that slavery may go to New York, to the home of the Pilgrim fathers, sweep along the shores of the great lakes, and darken the broad prairies of the West, under the sanction of this vested right of property in slaves under the Constitution.”

Mr. Chairman, if it be disingenuous to speak the truth, and speak it sincerely, if it be disingenuous to say we have a Constitution, and are entitled to its guarantees; if it be disingenuous to say we have rights, and ought to demand their enjoyment and insist on their protection, then, that gentleman was right in characterizing what I said as disingenuously bold. He, like others of his party, speaks of our claim for protection to slave property under the Federal Constitution as if it were a matter of surprise. I know not what such language as this, and that which refuses to recognize our right to property in negro slaves, means, unless those who use it expect to dragoon us, by their unblushing impudence and arrogance, into an abandonment of our rights and the adoption of their sickly sentimentality, as a substitute for reason and basis for statesmanship. My course towards others on this floor has entitled me, I trust, to a less offensive designation of what I say than “disingenuous.” And inasmuch as I sat by and listened to the whole of the gentleman’s speech respectfully, and no such expression was then used, he ought not to have put it in his printed speech.

But I leave this and say a word as to other points in this extract of his speech. I have said all I wish to say as to the destruction of private property, without compensation to the owner and against his wish, being a revolutionary act. He produces some confusion, by the singularity of his expression, in referring to what he supposed to be my position, that the claim of slavery to “protection under the Federal and State authority rests upon the same right as all other kinds of property/” I was not discussing the question as to any present necessity for legislation to protect slave property. Though, of course, the arguments I have presented to show that neither Congress or a Territorial Legislature can abolish it in a Territory, would, if correct, also show that if any legislation is necessary to its protection it is the duty of the Territorial Legislature to afford that protection, and, if it fail to give it then it would be the duty of Congress to give it. But I am at a loss to know what he can mean by its protection “by State authority” in connection with Federal authority. Slavery is only entitled to protection under State authority where it exists. It receives no protection, and needs none, from Federal Government in the States. It is entitled to the protection which all other property receives in the Territories. And if this is not given when needed, by the Territorial Legislatures, it ought to be given by Congress.

But there is one sentence of this extract of the gentleman’s speech which I will read again, to give it conspicuity. It is this:

“Then it is that slavery may go to New York, to the home of the Pilgrim fathers,, sweep along the shores of the great lakes, and darken the broad prairies of the West, under the sanction of this vested right of property in slaves under the Constitution.”

When? When the governments of the States where it exists protect within their own borders? How will this take slavery to New York, inflict it on the homes of the Pilgrim fathers, and sweep the great lakes, and darken the western prairies with it? Again, I ask, when? When the Territorial Legislature, or Congress, shall give it the protection to which it may be entitled in the Territories? No; not then. For New York is not a Territory, nor is New England, nor are any of the States which border on the great lakes, or cover the northwestern prairies. I have never said that the federal Federal Constitution would protect slavery in a State against its authority. Nor do I suppose any man in the Republic has ever assumed any such position. I have expressly and repeatedly declared, on former occasions, during this session, and that the people of the States could abolish slavery within their own jurisdiction, without any infractions of the Federal Constitution; and that it was a question with which the Federal Government had nothing to do in the States. When, then, under any doctrine I have propounded, can the gentleman’s dreadful catastrophe occur?

As I have spoken of the power of Congress to protect slavery in the Territories, I must say a word more to avoid being misunderstood. I have said Congress has the power, and that circumstances may render the exercise of that power necessary, But I am not discussing this question now, and do not wish to be understood as saying there is any necessity for its exercise at this time. Slavery is not expected to go into Washington or Nebraska or Kansas Territories; and hence no laws are necessary for its protection there. It now exists, to a limited extent, in Nw Mexico and Utah. In New Mexico the Territorial Legislature has passed the necessary laws for its protection; and in Utah there is no complaint of a want of additional protection. This covers all our Territories, and shows that no legislation is now necessary on the subject.

In support of the position that owners of slaves have a vested right of property in them; that the Territories are the common property, and slave property is entitled to the same protection in them as other property, I give the following extract from the late message of the President of the United States:

“I cordially congratulate you upon the final settlement by the Supreme Court of the United States of the question of slavery in the Territories, which had presented an aspect so truly formidable at the commencement of my administration. The right has been established of every citizen to take his property of any kind, including slaves, into the Common Territories belonging equally to all the States of the Confederacy, and to have it protected there under the Federal Constitution. Neither Congress nor any Territorial Legislature, nor any human power, has any authority to annul or impair this vested right. The supreme judicial tribunal of the country, which is a coordinate branch of the Government, has sanctioned and affirmed these principles of constitutional law, so manifestly just in themselves, and so well calculated to promote peace and harmony among the States.”

I know that the Republicans habitually affect to sneer at the opinions of the President, impugn his motives, and deride his capacity. The country will judge with what propriety and justice this is done; in view of his high character, great intellect, and unusual endowments; in view of the commanding position he has occupied before the American people for the past forty years; first as a Representative in Congress of the first mark; then as a Senator, the associate and peer of such Senators as Clay, Webster, Calhoun, Wright, and Benton, and always equal to the most difficult questions of his times; then as Secretary of State, conduction the affairs of that office during the splendid administration of Mr. Polk with consummate ability; then as Minister to Great Britain, where his conduct challenged the approval of his own Government, and commanded the respect of the first Court of the world; and in view of the fact for his great integrity, great ability, and great services he has been chosen President of the United States.

Sir, with such a past, and in view of the fact that he has, in advance, declined to be a candidate for reelection; when we reflect that the measure of his fame will be completed with his current term of service; that, under the ordinary rules of human conduct, he has no motive to be wrong on any question, but every possible incentive of duty, of patriotism, of personal pride and ambition, to leave behind him an unblemished history of purity, patriotism, and statesmanship, it would seem his opinions ought to be received with decent respect, and controverted upon their reasons rather than met with affected sneers at their alleged weakness and imputations upon the purity of his motives. And especially so when they are founded on, and sustained by, the opinions of the Supreme Court of the United States. But, sir, who could expect, in coming in conflict with the doctrines of a party which lives upon fanaticism and sectionalism, to escape its illiberal malignity?

I have not agreed with the President in all his views and recommendations; and do not now agree with him in all of them. But I can differ with him in opinion, and at the same time respect his motives, his wisdom, and his virtues. And when I find myself differing in opinion with him I am much more inclined to suspect my own judgment and want of experience, than his statesmanship and purity of purpose. Yet, sir, when I find my opinions conforming to those of such a man, I am willing to trust them, and on them to reject the mad schemes of Republicanism.

Chief Justice Taney, in delivering the opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott case, after demonstrating with such clearness and precision as to defy doubt, that the persons of the African negro race were not “citizens” of the United States, or “people” in the sense in which these words are used in the Declaration of Indepedence, and in the Constitution of the United States, to describe and regulate the status, franchises, and duties of citizens of the United States, goes on to say, speaking of them that—

“The only two provisions which point to them and elude them, treat them as property, and make it the duty of the Government to protect it; no other power, in relation to this race, is to be found in the Constitution; and as it is a Government of special, delegated powers, no authority beyond these two provisions can be constitutionally exercise. The Government of the United States had no right to interfere for any other purpose but that of protecting the rights of the owners, leaving it altogether with the several States to deal with this race, whether emancipated or not, as each State may think justice, humanity, and the interests and safety of society require. The States evidently intended to reserve this power exclusively to themselves.”

In another part of the same opinion he says, in speaking of the power of the Federal Government to acquire and control territory:

“Whatever it acquires, it acquires for the benefit of the people of the several States who created it. It is their trustee acting for them, and charged with the duty of promoting the interests of the whole people of the Union in the exercise of the powers specially granted.”

And again, in the same opinion, speaking of the territory acquired from France, he says:

“But as we have before said, it is acquired by the General Government, as the representative and trustee o the people of the United States, and it must therefore, be held in that character for their common and equal benefit; for it was the people of the several States acting through their agent and representative, the Federal Government, who in fact acquired the territory in question, and the Government holds it for their common use until it shall be associated with the other States as a member of the Union.”

And, after showing that the right of the Federal Government to govern the Territories is ‘the inevitable consequence of the right to acquire territory;” and that it may exercise its discretion as to the form of government best suited to the interests of the people of a Territory, he says:

“The territory being part of the United States, the Government and citizens both enter it under the authority of the Constitution, with their respective rights defined and marked out; and the Federal Government can exercise no power over his person or property beyond what that instrument confers, nor lawfully deny any right which it has reserved.”

As to the assumption of the power by Congress to discriminate between slaves and other property in the Territories; as to the extent of the power of the Federal and Territorial governments over the rights of person and property in the Territories; as to the extent of the power of the Federal and Territorial governments over the rights of person and property in the Territories; as an answer to the assumption that there is a difference between slave and other property, and that different rules may be applied to it in expounding the Constitution of the United States, and as a distinct affirmation of the doctrine of the right of property in slaves, I will read the following extended extract from the same opinion, and, without reference to the exalted character of the character of the tribunal which pronounced the opinion, will rest

upon the answerable force of its reasoning, as conclusive on the points discussed:

“But the power of Congress over the person or property of a citizen can never be a mere discretionary power under our Constitution and form of Government. The powers of the Government and the rights and privileges of the citizen are regulated and plainly defined by the Constitution itself. And when the Territory becomes a part of the United States, the Federal Government enters into possession in the character impressed upon it by those who created it. It enters upon it with its powers over the citizen strictly defined, and limited by the Constitution, from which it derives its own existence, and by virtue of which alone it continues to exist and act as Government, from which it derives its own existence, and by virtue of which alone it continues to exist and act as a Government and sovereignty. It has no power of any kind beyond it; and it cannot, when it enters a Territory of the United States, put off its character, and assume discretionary or despotic powers which the Constitution has denied it. It cannot create for itself a new character separated from the citizens of the United States, and the duties it owes them under the provisions of the Constitution. The Territory being a part of the United States, the Government and the citizen both enter it under the authority of the Constitution, with their respective rights defined and marked out; and the Federal Government can exercise no power over his personal property, beyond what that instrument confers, nor lawfully deny any right which it has reserved.

“A reference to a few of the provisions of the Constitution will illustrate this proposition.

“For example, no one, we presume, will contend that Congress can make any law in a Territory respecting the establishment of religion, or the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech or of the press, or the right of the people of the Territory to peaceably assemble, and to petition the Government for the redress of grievances.

“Nor can Congress deny to the people the right to keep and bear arms; nor the right to trial by jury; nor compel any one to be a witness against himself in a criminal proceeding.

“These powers, and others, in relation to rights of person, which it is not necessary here to enumerate, are, in express and positive terms, denied to the General Government, and the rights of private property have been guarded with equal care. Thus the rights of property are united with the rights of person, and placed on the same ground, by the fifth amendment to the Constitution, which provides that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, and property, without due process of law. And an act of Congress which deprives a citizen of the United States of his liberty or property into a particular Territory of the United States, and who had committed no offense against the laws, could hardly be dignified with the name of due process of law.

“So, too, it will hardly be contended that Congress could by law quarter a soldier in a house in a Territory without the consent of the owner, in a time of peace; nor in a time of war, but in a manner prescribed by law. Nor could they by law forfeit the property of a citizen in a Territory, who was convicted of treason, for a longer period than the life of the person convicted; nor take private property for public uses without just compensation.

“The powers over person and property, of which we speak, are not only not granted to Congress, but are in express terms denied, and they are forbidden to exercise them. And this prohibition is not confined to the States, but the words are general, and extend to the whole territory over which the Constitution gives it power to legislate, including those portions of it remaining under territorial government as well as that covered in States. It is a total absence of power everywhere within the dominion of the United States, and places the citizen of a Territory, so far as these rights are concerned, on the same footing with the citizens of the States, and guards them as firmly and plainly against any inroads which the General Government might attempt, under the plea of implied or incidental powers. And if Congress itself cannot do this—if it is beyond the powers conferred on the Federal Government—it will be admitted, we presume that it could not authorize a territorial government to exercise them. It could confer no power on any local government, established by its authority, to violate the provisions of the Constitution.

“It seems, however, to be supposed that there is a difference between property in slave and other property, and that different rules may be applied to it in expounding the Constitution of the United States. And laws and usages of nations, and the writings of the eminent jurists upon the relation of master and slave, and their mutual rights and duties, and the power which Governments may exercise over it, have been dwelt upon in the argument.

“But, in considering the question before us, it must be borne in mind that there is no law of nations standing between the people of the United States and their Government, and interfering with their relation to each other. The powers of the Government, and the rights of the citizen under it, are positive and practical regulations plainly written down. The people of the United States have delegated to it certain enumerated powers, and forbidden it to exercise others. It has no power of the person or property of a citizen but what the citizens of the United States have granted. And no laws or usages of other nations, or reasoning of statesmen or jurists upon the relations of master and slave, can enlarge the powers of Government, or take from the citizens the rights they have reserved. And if the Constitution recognizes the right of property of the master in a slave, and makes no distinction between the description of property and other property owned by a citizen, no tribunal, acting under the authority of the United States, whether it be legislative, executive, or judicial, has a right to draw such a distinction, or deny to it the benefit of the provisions and guarantees which have been provided for the protection of private property against the encroachment of the Government.

“Now, as we have already said, in an earlier part of this opinion, upon a different point, the right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution. The right to traffic in it, like an ordinary article of merchandize (sic) and property, was guarantied (sic) to the citizens of the United States, in every State that might desire it, for twenty years. And the Government, in express terms, is pledged to protect it in all future time, if the slave escapes from his owner. This is done in plain words—to plain to be misunderstood. And no word can be found in the Constitution which gives Congress a greater power over slave property, or which entitles property of that kind to less protection than property of any other description. The only power conferred is the power coupled with the duty of guarding and protecting the owner in his rights.”

How do the Republicans meet reasoning like this? Is it by an examination and exposition of the provisions of the Constitution? Is it by a fair statement and lucid exposition of the facts of our political history? Is it by the searching power of analysis, and the convincing force of sound logic? No, sir; by none of these. But by a demurrer to the jurisdiction of the court, and by an ad captandum declaration that it is the opinion of Democratic and pro-slavery judges on a political question, and by broad, bold, audacious charges of contrivance and corruption. Thus taking a double appeal from the decision of the august tribunal of last resort which such questions are referable under the Constitution; the one an appeal from the Supreme Court of the United States to the political clubrooms and hustings; the other an appeal from the reason and conscience and judgment of a bench of great, good, and learned judges, to the ignorance, passions, and bigotry of deluded fanatics. Sir, this is the most alarming testimonial of the decadence of public virtue and patriotism, and of the impending peril to our system of free self-government and well-regulated civil and religious liberty.

Suppose some members of the court are Democrats. Is that a fact sufficient to throw suspicion on their integrity and doubt upon their reasoning? A large majority of the American patriots and statesmen of the past were of that political party. And suppose some of them may be slaveholders: does this change the meaning of the Constitution, and answer facts and overturn logic? Washington and Jefferson, and Madison and Monroe, and Jackson and Polk, and Marshall and Clay, and Calhoun and Benton, were all slaveholders. Were they, on that account, less wise, less patriotic, and less trusted by the Republic? But the truth is, that the venerable Chief Justice, many years ago, liberated all of his slaves; and from this fact I would infer that, if he had any prejudice in such a case, it would be against the interests of slavery. And this fact is a sufficient answer to the charge that he is a pro-slavery judge.

It was the opinion of the court that both the question of jurisdiction and the judgment of the circuit court were brought before them by the writ of error, and that they were bound to pass upon both. And though two out of the nine judges dissented from this opinion, the court stood divided as two to seven on the question. I will not speak of the political opinions of the two dissenting judges; for this would be to impugn the integrity of their motives, and to follow the vicious and dangerous example of the Republican party. But they will see how such an argument, in the hands of men having no higher confidence in the purity of the Supreme Court of the United States than themselves, could be turned against them. I will not consume time by giving the arguments and authorities adduced by the majority of the court in support of their view of this question. It is accessible to lawyers generally; and few others than they would feel an interest in examining questions of pleading and jurisdiction. And I only refer to it this far as to say that, in charity, I am led to hope the men who have so often, in this Hall, denounced the majority of the court in terms of such bitter reproach and condemnation, have never read the opinion and judgment of the court, or, if they have read it, have no understood it. The presumption that they act ignorantly would excuse them with contempt; while the supposition that they understand what they do, might, in history’s future impartial judgment, set them down as willful calumniators of great and good men.

Why; sir, if there is a class of men in the Republic who are entirely out of the reach of political partisan dependence and motives, and above the reach of popular clamor, it must be the Federal judges. And their very vocation is a continual schooling of both the mind and conscience in all the higher and nobler duties of life. And I do not envy the man who stakes his legal reputation in the contest against the opinions of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case, or his character for truth and honor upon an assault on the integrity and purity of its judges.

This much I have felt my duty to say, on account of the repeated attacks which have been made here on the court in connection with this case. I do not say this to defend the reputation of the judges. Their venerable years, their lives of purity and honor, their great learning, and the exalted position they occupy, and the country’s confidence, is their defense. But I have said to expose the efforts which have been made by the Republican party to mislead the public mind on great questions, by unfair and unjust attacks on a coördinate branch of the Government, rightfully acting within the sphere of its own duties.

Mr. EDGERTON took the floor.

Mr. MORRIS, of Illinois. With the gentleman’s consent, I will propound an interrogatory to the gentleman from Texas.

Mr. EDGERTON. I will yield if it will not be taken out of my time, for I want all of the hour to which I am entitled.

The CHAIRMAN. If there be no objection, it will be considered as the understanding of the committee that, if the gentleman yields, it will not be taken out of the gentleman’s hour.

There was no objection.

Mr. MORRIS, of Illinois. The President of the United States, in his letter accepting the nomination of the Cincinnati convention, alluding to the Kansas-Nebraska bill, said that legislation giving to the people of organized Territories the right to determine the question of slavery for themselves was as ancient as free government itself. The President at the same time declared that the people of a Territory, like those of a State, have the right to decide for themselves upon the question of slavery within their own midst. Now, the question I ask is this: what did the President mean by that language?

Mr. REAGAN. I am apprised of the gentleman’s quarrel with the President, and not desiring to interfere in it, I leave the words for every gentleman for himself to construe.

Mr. MORRIS, of Illinois. That is a queer way to answer, and yet it is about the only answer that can be made. If I have a quarrel with the President, it has nothing to do with the proper construction of the language I have referred to. When the gentleman from Texas undertakes to quote the President, I think he ought to quote his whole record, and not garbled extracts from it.

Mr. REAGAN. It runs through forty years, and I could not possibly put it all in an hour’s speech.

Mr. MORRIS, of Illinois. Give us, then, his record for the past four years, and it will do. The more of it we could have, the worse it would be for him.

[…] John T Reagan, with a nearby county [link] and elementary [link] in Ector County Independent School District named after him had this to say: [paper] [source] [full text] […]

LikeLike