You’ll often hear, in reference to current events, that the Republican Party has its origins in the anti-slavery movement of the mid-19th century.

This is, strictly speaking, true, but bowdlerized.

The best an abolitionist Liberty Party candidate ever did for president was 2.3 percent of what was then the popular vote in 1844.

The Free Soil Party was anti-slavery but only in so much as it disliked enslaved people. It got 10.1 percent in 1848.

The Know Nothing Party didn’t care for slavery but what really got it going was anti-immigrant nativism, contemporarily aimed at Irish and German Catholics. In 1856, it got 21.5 percent of the vote, still only good for third. By then, the Republican Party was competing on a slogan of “Free soil, free silver, free men.”

Abraham Lincoln won the presidency as a Republican with less than 40 percent of the popular vote four years later.

At that time, most white Americans who were inclined to view slavery as a problem chose to blame the enslaved people for the results of their exploitation rather than their slavers. Many native-born felt compelled to recoil at the conditions recent immigrants experienced in the depths of poverty around them but despised such people for enduring it. If you have ever resented a homeless person for smelling of mildew next to you at a coffee shop rather than the circumstances that led to them being outside in damp and dreary conditions, you’ll understand how insidious and unhelpful this impulse is.

In what might unfairly be called the Oregon View, there has always been a strain of the Left that comes to the conclusion that America’s problems can be solved by aligning against the vulnerable and forcibly expelling or further marginalizing them.

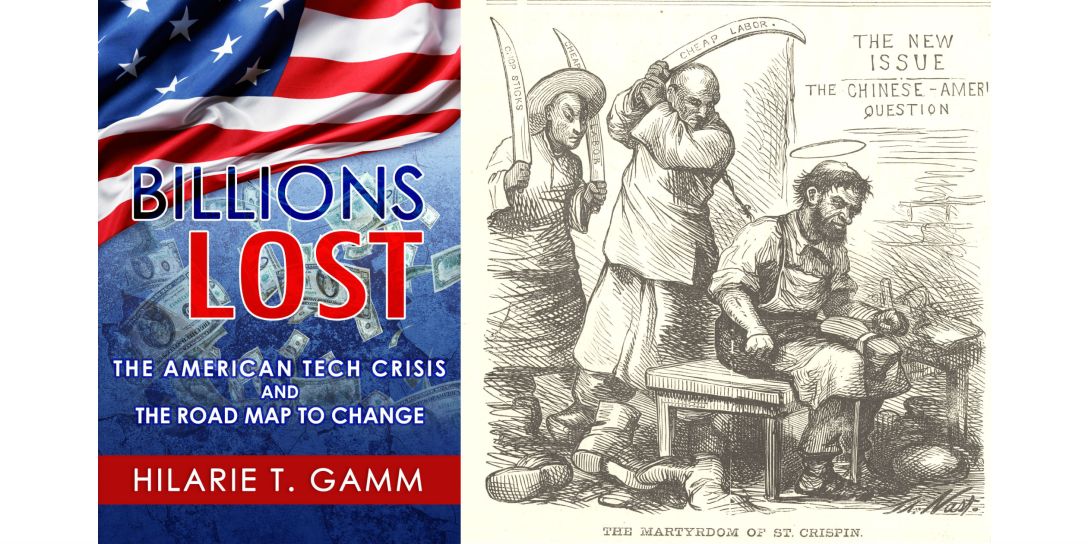

Make it illegal for black Americans to stay in the area without having to suffer violence. Make it illegal for Chinese Americans to return to the home they’ve made for decades, even if the person just created the most popular cherry in the United States. The fruit of his ingenuity and hardwork—Ah Bing’s namesake—could stay, but not the person.

Oregon is an easy target but so would be Tacoma. Or any sundown town. Or anywhere in America at any time.

It appears in some surprising places. Here’s a modern American politician treating humans from some other place as an infectious Other in reaction to the idea of loosening immigration levels and embracing foreign workers.

It would make everybody in America poorer — you’re doing away with the concept of a nation state, and I don’t think there’s any country in the world that believes in that. If you believe in a nation state or in a country called the United States or UK or Denmark or any other country, you have an obligation in my view to do everything we can to help poor people. What [some] people in this country would love is an open-border policy. Bring in all kinds of people, work for $2 or $3 an hour, that would be great for them. I don’t believe in that. I think we have to raise wages in this country, I think we have to do everything we can to create millions of jobs.

You know what youth unemployment is in the United States of America today? If you’re a white high school graduate, it’s 33 percent, Hispanic 36 percent, African American 51 percent. You think we should open the borders and bring in a lot of low-wage workers, or do you think maybe we should try to get jobs for those kids?

That’s Bernie Sanders in 2015, by the way. He said “right wing” rather than “some” people want open borders, but he continued to demonstrate an essentialist view of nationality.

Sanders goes on to say, “I think from a moral responsibility we’ve got to work with the rest of the industrialized world to address the problems of international poverty, but you don’t do that by making people in this country even poorer,” which again, falls right in line with the idea that someone in the United States originally from somewhere else is in immutable essence of that other place rather than in the process of making themselves of this place by virtue of moving here, living here, going to school here, working here, making a home for themselves and their families here.

This is still (is actually?) a book review of Hilarie T. Gamm’s Billion’s Lost: The American Tech Crisis and the Roadmap to Change. I don’t have much to say about it. It’s a bad book, and in any just world that valued empathy, it would be universally be regarded as such. Instead we live in this one, and I know it has some appeal.

Gamm (a pseudonym) may have been misinformed and thought the Cascadia Advocate was related to some other movement, rather than the Northwest Progressive Institute.

But this is not the Steve Bannon Book Club.

“A country is more than an economy. We’re a civic society.”

This is the justification Bannon would give for keeping non-white immigrants out of the United States, even when they’re contributing a net gain in any measurable sense. Good on him for avoiding all dissembling to get right to the heart of white nationalism, though. It’s not the legalism or the process or the idea of a net drain: it’s that the only people he wants here are white, culturally “Judeo”-Christians.

Gamm at least starts from a place of greater sympathy because the supposed subject and target of Billions Lost is the H-1B visa program.

The specialty occupations that temporary foreign workers are supposed to be filling aren’t necessarily so special at all. The program gives corporations, particularly those in the tech industry, a strong club to beat domestic tech workers with, something they’re keen to do after the class-action lawsuit Vizcaino v. Microsoft of the late 1990s gained domestic workers more protections.

This first portion of the book tracks the history of the U.S. tech industry, showing how regulations requiring employers to treat their American workers fairly sent companies down a path of least resistance looking for workers easier to exploit and mistreat. It acknowledges how rising education standards, globally but particularly in English-speaking India, created an alternative workforce willing and able to do work more cheaply with less stringent protections.

So, the legitimate problem and more fundamental scariness represented by a Y2K catastrophe was an excuse to utilize a lot of temporary foreign workers to fix one big problem, and corporations continued to use such workers long after that emergency had disappeared. The corporations benefitting most from the program made no noise about stopping it, and in the 21st Century, there were no unions of any strength to make noise. No issues there.

But it’s at this crossroad after identifying a problem that progressives and reactionaries fundamentally diverge.

The YouTube creator Olly Thorn provided an optimistic frame for why the Left, generally, has the stronger case for the future. A progressive sees the most vulnerable people in a system and looks for ways to make common cause with each other against some oppressive force, to be stronger by mutual support.

A reactionary looks for ways to use someone else’s weakness as a way to define the vulnerable as separate from and lesser than a more self-sufficient group that the audience of course always imagines being included in.

That’s where this book takes its turn into a bad trip, and where the American Left has traditionally struggled.

Gamm says that restricting foreign workers is the best solution to help them not be exploited, but really to help native U.S. tech workers like her. This is in contrast to the more natural solution: empower those new residents to be independent and give them the sort of protections that would align with other U.S. laborers—that is, to be able to regard themselves as fully American.

Gamm disabuses the reader of any idea that this is an innocent mistake or one born of harmless ignorance by making it unmistakably clear she dislikes the idea of F-1 visas and foreign students in American universities, too.

Here are some of the complaints Gamm gives for why universities should accept fewer non-native students:

- An anecdote from one Chinese student that “90 percent” of Chinese students like to hang out with fellow Chinese students instead of socializing with other groups because they have nothing in common.

- A reference to a 2005 New York Times article summarized as foreign graduate students having thick accents and not speaking English well enough to teach.

- A regurgitation and extension of a Malcolm Gladwell argument in “Rice Paddies and Math Tests” that the culture of Chinese rice farming and acceptance of authoritarianism means the foreign students have a natural predilection for STEM fields that favor rote memorization and practice, something an American focus on “ingenuity” and history of mechanical corn farming can’t fairly compete with.

- This direct quote: “Math, science, and computer majors hold less appeal for those marriage-minded heterosexual young men who hope to meet a potential mate for life during their college studies.”

That’s a literal, if tossed-off, argument the book makes, which, if we’re not in 14 words territory yet, we’re definitely seeing the road signs for the off-ramp to it.

Look, this is not a good book, but that’s a lucky thing because it would not have been so hard to sand off these rough edges and make it the sort of book other political figures on the Left would have felt the impulse to conduct apologetics for as not necessarily racist, just reflecting the sort of thing white people naturally feel uncomfortable about.

Without the references to participation trophies, lazy Millenials, and full-throated endorsement of charter schools, this could have been the sort of book that lulled unsuspecting folk into thinking it had anything useful to say. Luckily, Gamm included all of that and peddled a conspiracy that Chinese students are all spies taking American intellectual property back to the Middle Kingdom to make fools of us all.

This is an aside in an already digressive piece, but how much of an idiot do you have to be to examine the relationship between other nations and the U.S. university system and not recognize it as the greatest force of soft power we possess?

It’s not even fair. Repressed, wealthy foreign nationals come to U.S. colleges and experience the best years of their life because they can surf an uncensored Internet and express divergent political opinions with impunity—oh and they’re also young, as healthy and attractive as they’ll ever be.

For the literal entirety of the rest of their lives, these former students will look back on their time in the United States as the best years they ever had, and a not-insubstantial portion will pine to move back and recapture their lost nostalgia.

If you want to solve the H-1B program, give workers the sort of visa that allows them to work anywhere they want to, unionize just like the native-born, and fulfill their aspirations to become Americans. If you want to make U.S. colleges more welcoming to already-American students, fund public tertiary education so they don’t have to go into crippling debt to pursue STEM fields deeper. This is not difficult.

You don’t restrict who gets to come to America: you expand what it means to be an American. You actually help people instead of punishing some Other you’ve just defined. If your roof leaks when it rains, fix the roof.

I’m not as optimistic as Olly Thorn. I think folks will always find it easier to shore up their insecurities by pointing at someone else and arguing some essential quality of those people makes them worthy of scorn, Pap Finn-style.

But we can do better. We have to do better. Not just for tech workers we think can help us in the Brain Drain sense but for those we despise for their weakness and assume can’t help anyone. Bannon has already admitted the distinction is irrelevant. We should too.

A temporary-foreign-worker program that allows and requires those workers to work only for one company in order to make money—and be deported if the company says they broke the terms of their contract—is not slavery, but the choice of destitution for a person and their family set against sexual harassment, physical abusement, or fatal illness is not a fair one for workers to have to make. That’s for any workers, from any place working any where in America.

That’s where our empathy ought to be. That’s where our focus on providing guarantees ought to remain.

Jesus said, “As you do to the least of these, you did to me.” We have to make sure that’s important to us whether we’re talking about the one from Nazareth or Michoacán, and whether a Lee was born in Shanghai or Mobile.

We have to do the work of climbing on the roof to fix the leak, not just shove someone out into the rain to feel drier by comparison.

[…] theme, appearing again and again in labor history, is how when labor divides against itself, it can’t succeed. The mill girls didn’t have the support of their male counterparts, so their leverage against […]

LikeLike